So says Orson Welles in this clip from F for Fake. I couldn’t help but think of Welles and his film when reading Martin Gayford’s piece on the National Gallery in London’s new exhibition “Close Examination: Fakes, Mistakes and Discoveries”.

Gaysford asks “whether works of art are really by the people or cultures that are supposed to have created them?” The Exhibit at the National Gallery will examine these questions, with specific objects. One object which the exhibit draws on is “The Faun” a fake Gauguin sculpture created by Shaun Greenhalgh which fooled the Art Institute in Chicago (and many others) for a number of years. Gaysford notes that after Greenhalgh’s deception was discovered, we all thought very differently about the object, when in fact “this changed nothing. The faun remains the same pointy-eared, hook-nosed fellow that he always was.” Yet Gaysford notes:

The point of this story is not that art experts are foolish. In fact, the Faun is a very clever forgery. Its brilliance in part is that there actually was a Gauguin sculpture of a faun – it’s listed in an old inventory and may still exist in a cupboard somewhere. The lesson is that now we know it’s not a Gauguin, it ceases to be part of a larger whole: Gauguin’s art. At that point, even if it is still quite an attractive statuette, it loses an enormous amount of meaning. Discovering a work is a fake is like discovering a friend has been lying to you for years.

It is difficult to separate the object from the deception. Even if the faun was a terrific work of aesthetic beauty, the fraud which spawned the forgery taints that beauty in our mind—we might even resent the object the better the “fake” really is. That is not to say it cannot be a beautiful object, but it loses something by trying to trick us.

|

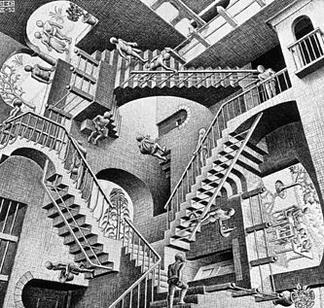

| Relativity, M.C. Escher, 1953 |

Artists play tricks all the time. The works of M.C. Escher may be the most obvious examle of this. But his deception is mathematical, and there for you to see—in a sense the job of the viewer is to try to figure out how he has done it. Orson Welles was right to ask what’s in a man’s name, and right to point out that it may not matter that much. But what does matter for something like the Faun and other forgeries is the lie told to the audience or the buyer. Art forgers may be the creator of the work, but also those who attempt to pass off works they know or should know are forged on an unsuspecting public.

The bigger question is how many forgeries are exhibited in museums alongside the authentic works. When buyers and sellers and museums are not careful about the history of an object (including antiquities) we might think of them as a kind of forger as well. They may be unwitting, and fooled by a clever forger as the Art Institute of Chicago was, but when they value the object above everything, they risk becoming complicit in the forgery.

- Martin Gayford, Art forgeries: does it matter if you can’t spot an original?, Telegraph.co.uk, June 17, 2010, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/art/art-features/7824999/Art-forgeries-does-it-matter-if-you-cant-spot-an-original.html (last visited Jun 18, 2010).