Category: Uncategorized

Seminar Paper: William M. V. Kingsland and the Importance of Provenance

I’m publishing here a series of papers written by law students in my ‘Property, Heritage and the Arts’ seminar from the Fall of 2009. This paper was written by Michael Poché

1. Introduction

Nature, left undisturbed, so fashions her territory as to give it almost unchanging permanence of form, outline, and proportion, except when shattered by geologic convulsions. . . . In countries untrodden by man, the proportions and relative positions of land and water. . . are subject to change only from geological influences so slow in their operation that the geographical conditions may be regarded as constant and immutable. Man has too long forgotten that the earth was given to him for usufruct alone, not for consumption, still less for profligate waste. . . But she has left it within the power of man irreparably to derange the combinations of inorganic matter and of organic life. . . man is everywhere a disturbing agent. Wherever he plants his foot, the harmonies of nature are turned to discords. . . [O]f all organic beings, man alone is to be regarded as essentially a destructive power….

George Perkins Marsh, The Earth as Modified by Human Action: Man and Nature [fn1]

When George Perkins Marsh first penned those words in 1874, he was speaking in his role as one of America’s first important environmentalists. Contrary to the prevailing notions of his contemporaries, Marsh felt that, rather than being owners of the earth – as in the traditional Abrahamic concept of property – we are in fact only stewards of the earth, here for a short time only, and that instead of practicing some supposed birthright over the land, we were instead bound by a birth “duty”, so to speak, to protect it.

Though his expertise was in the environment (as well as diplomacy and philology), Marsh may as well have been speaking about the art world; the philosophy of guardianship he espoused towards the Earth would serve us well as a basic model for how humankind should safeguard its cultural riches. One of the few things which can be said with some certainty about art is that nearly every culture throughout human history has spent time creating works which are largely decorative in nature; the big question is, “Why?” While we still do not possess an all-encompassing answer to that question, the question itself is strongly suggestive that the creative act, in its myriad forms, is some form primal human strategy, on par with survival, sustenance, procreation, etc.

It is here that the comparison to Marsh’s quotation becomes problematic; Marsh saw man as “. . . essentially a destructive power.”[fn2] This is true, but he is also the only consciously creative power as well. Because of this dual nature, it is important to ensure that our destructive tendencies do not overshadow our creative ones. Now, clearly, not every person has a creative (or rather, artistic) bent. For some of those who do not, art may be nothing more than a blank slate; some may be appreciators, either highly opinionated or more catholic in taste; but some have an almost hostile stance towards art, which could manifest itself in numerous ways.

Much environmental advocacy is practiced from a state of naiveté and pessimism; that is, we don’t know what the long range effects of our actions will be – and we are assuming that our actions and their effects will be negative – so a prudent course would be to treat our environment as cautiously as possible. And so it should be with our cultural heritage: because we don’t fully understand why people have always made art, it would behoove us to assume that the fact of its universality indicates its importance to our existence. As we are only stewards of this Earth, so too are we stewards of our cultural legacy.

One of the primary tools we have at our disposal to this end is that of provenance. Provenance acts as a sort of cultural lineage, or a chain of succession. It ensures the integrity and value of art, as well as provides a guidepost of authenticity. It is especially important when purchasing art; potential buyers need to be made aware of a piece’s particular history, and failure to be able to do so should be a big red flag to purchasers, be they newbies or long time connoisseurs.

So, what to say of someone who, despite an obvious love for art, so eradicates the provenance of, not one or a few, but of close to three hundred valuable pieces[fn3] that they end up languishing in the hands of the F.B.I., awaiting either return to their rightful owners or an uncertain fate on the auction block, where disinterested relations of the previous “owner” hope they will eventually end up?

2. The Mystery of William M. V. Kingsland

On March 21 2006, the body of William Milliken Vanderbilt Kingsland was discovered in his apartment on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, dead of a heart attack; he was later estimated to be 62 years of age. On April 13 of that same year, an article which appeared in The New York Sun painted a portrait of a man almost genetically enhanced to appear in the dictionary next to the entry for “eccentric” or “character:

With a wry Cheshire cat smile, Kingsland cut a striking figure among the interlocking worlds of historic preservationists, galleries, and the gavel set of New York auction houses. . . “The thing about Kingsland was that he was slightly annoyed that the 20th century had occurred.” . . . His particular metier was the minutiae of the lives in Upper East Side buildings over generations. . . [H]e arguably made his greatest contribution by piecing together connections between cemetery vault purchasers and their living descendants. . . This flaneur was known to stop friends on the sidewalk and seemed to have all day to talk. He did not appear to have to be anywhere unless he decided to be there. He had leisure to deliver correspondence personally, too. . . In successive apartments on East 78th and 72nd Streets, friends recalled floor to ceiling paintings, some stacked against each other more for protection than for show. Shelves of books competed for space with folded tapestries, bibelots, objets de vertu, snuffboxes, bronze items, and illuminated manuscripts peering out of boxes. . . Reliquaries may have been kept in the dishwasher, and a Giacometti used as a doorstop. While he said his East 72nd Street apartment was for storage, it is unclear where his primary residence was. . . Kingsland worked at Vito Giallo Antiques on Madison Avenue three days a week from 1986 to 1991. Singer Elton John was so enchanted with Kingsland that he left a blank check for him to fill out for 19th-century statues. Andy Warhol befriended Kingsland for a time. At lunchtime at the store, Kingsland ate two jars of Gerber baby food. . . A longtime preservationist, Tony Wood, said there was an “air of delightful mystery around him.” Though he said he had attended Groton, the school has no record of him.[fn4]

The stories about Kingsland go on and on: writing about art for Art/World and Art + Auction; he had reportedly once been married to French royalty[fn5]; alternatively, he claimed to have been descended from long dead French royalty[fn6]; as a young man he had attended Harvard University[fn7]; and on and on.

– – – – –

Of course, it was all too good to be true. The fact that during his lifetime he was known to have used the Giacometti he possessed as doorstop – a statute which was later estimated to be between $900,000 and $1,200,000 in value[fn8] – should have been a big warning flag to anyone who may have visited his home; perhaps they were too enchanted by his quirky charms to care. For his own good and that of his “fans”, it may be just as well that the unraveling of the Kingsland mystique only began after his death.

It began with the discovery shortly after his death that Kingsland had left no will, and at the time appeared to have no living relations. Then, just a few months after his death, it was discovered that Kingsland was not “William Milliken Vanderbilt Kingsland” but actually one Melvyn Kohn who lived, not on fashionable and tony Fifth Avenue as believed by those who knew him, but in fact a small, cramped apartment on 72nd Street. Two independent genealogical researchers, Leslie Corn and Roger Joslyn, apparently intrigued by the Kingsland/Kohn mystery, discovered that he had come, not from an aristocratic lineage as he asserted in life, but from refugee parents escaping from Europe; his father was from Austria and his mother was born in Poland. Rather than to the manor born, Melvyn Kohn was actually born at Park East Hospital in New York City in 1943. Unearthed records also reveal a more pedestrian education: rather than the upper-crust Groton Academy, Kohn actually graduated from the Bronx High School of Science in 1959. Later, Kohn spent some time at the NYU College of Arts and Sciences; there appears to be no record of his graduating, however.[fn9]

Most unusual of all is the story of how the mythical “William M. V. Kingsland” came into being. In some bizarre attempt to raise their son beyond his station, Kohn’s parents filed a motion for a legal name change in the hopes that a more aristocratic appellation would assist him in his pursuit of becoming a writer. One early example of his writing was a letter sent to The New York Times when Kohn was only 18 years old. The subject? Nothing more than the controversy surrounding the status of the Elgin Marbles; the irony and prescience of this topic as it relates to the later controversy surrounding his legacy should be apparent.

Kingsland died intestate; accordingly, the art in his private collection – which had filled his 245 East 72nd Street apartment from top to bottom and included works by Picasso, Giacometti, Copley, Morandi, Redon, and Gorchov, among many others – was slated to be auctioned off by order of the Public Administrator for New York[fn10]. Christie’s auction house and the Stair Gallery were chosen for the task, but before the auctions began, both of the esteemed art merchants discovered the shocking truth: during the standard pre-sale research of the artworks, many were discovered to have been reported as stolen, with the thefts going back as far as the 1960s.

At this point in time, no authority has been able to state unequivocally that Kingsland himself actually stole the works in question; indeed, no would-be Thomas Crown has yet been tied to the alleged thefts, nor has the mode by which the works came to be in Kingsland’s possession. To further complicate matters, many who had reported the works as stolen in the first place have since died, lost interest, or have been unable to be either identified or found. The final twist was the revelation of previously unknown relations of Mr. Kingsland; an uncle and four cousins have now come forward, claiming themselves as rightful heirs to the Kingsland estate.

But is the art in question inheritable? Though not all of the pieces in the collection have been listed as stolen, the very presence of so many with questionable provenance throws the legitimacy of the entire estate into question. As it now stands, all of the works which have been positively identified as reported stolen are in the possession of the F.B.I., awaiting their true owners to come forward.

– – – – – – – – – –

Of course, the mystery and confusion surrounding the collection is wholly of Kingsland’s own doing. As a self-styled expert on art, Kingsland surely must have realized that acquiring such works outside of legitimate legal channels would lead to eventual controversy upon his death, and that the possible effects on the work could be negative. As a semi-famous genealogist, one would think that Kingsland would appreciate the importance of a sound succession. Finally, as an art lover, Kingsland should have understand the disservice he was doing to the works in his possession.

What motivated him? Was there some frustration on his part over never having accomplished the lofty artistic agenda set up for him by has parents when he was young? Was he simply an obsessive-compulsive pack rat who got a charge out of stealing art, with little concern for its intrinsic worth? These are questions we’ll never be able to answer fully. The one thing we can say, however, is that because of his actions, the majority of the works in his possession have been deprived of their rightful place in the hands of those who had originally possessed them, and that they now face an uncertain fate at the hands of distant relations who have yet to voice any concern for the art other than their own personal interest in it. To follow through on the analogy voiced earlier in this essay, Kingsland is something of a plunderer of the earth, perhaps one who thought that hoarding a small stash of the art world’s riches secured him some place of importance. Kingsland for too long denied the art in his possession its rightful place in our cultural landscape; by doing so, Kingsland in a sense defiled the very art he supposedly loved.

– – – – – – – – –

The great unknown in this debacle is the fate which awaits the Kingsland lode. The potential heirs of the collection have (at least) two options before them: on the one hand, they could blindly fight for ownership of the art and, if successful, simply sell to the highest bidder. The other option would be to recognize that their claim to the stolen property is tenuous at best. One can hope that they would recognize the injustice of profiting from the criminal acts of a wayward relation.

Though small, there is a chance that the heirs of the Kingsland collection will do right by the art, either in the form of an en masse donation or the establishment of some private trust to ensure for the future of the works. In an odd sense, the total worth of the collection as a whole may be greater than the sum of the parts. Despite the controversy surrounding the collection – or perhaps because of it – Kingsland’s stash is now a singular entity. The disruption caused to the provenance of the works by Kingsland’s mischief may now best be rectified by keeping the collection intact, thereby returning a bit of the natural order to them that misfortune had deprived them of. It would not be completely unprecedented for the Kingsland heirs to take such a action; at least once fairly contemporary example could serve as a model for such a course of action.

3. The Sisto Collection

In 1958, John Sisto, a native of Bari, Italy, immigrated to the United States. Accompanying him was a small collection of antiquities, mostly old documents. He became something of a self-styled expert in ancient Latin and, despite his lack of education, came to be called upon as an expert by various universities in assorted subjects. He began to periodically receive shipments from Italy of assorted antiquities, mostly from his father: documents such as letters from King Charles V and King Ferdinand II, a statue collection known as the Canosa artifacts, and at least two papal documents from 1500s-1600s.[fn11]

Over the ensuing years, Sisto’s collection grew to over 3,500 pieces – some dating back as far as the 500 B.C.[fn12] – and the collection came to fill his Berwyn, Illinois home in large trunks covering the floors, and all the way up to the ceiling… is this starting to sound familiar?[fn13]

Upon his death, Sisto’s son, Joseph Sisto – who already harbored misgivings regarding the origins and source of the collection for some time – contacted the local police, and later the F.B.I., over his suspicions. Out of the 3,500+ items in the collection, the F.B.I. determined that approximately 1,600 of the items had been illegally removed from Italy. During the course of his studies, the younger Sisto became aware of a treaty enacted by UNESCO in 1970 which asserts that items of cultural importance should be returned to their country of origin; to this end, he requested that the questionable property be repatriated back to Italy.[fn14]

There are some who question the validity of Italy’s claim to the property; art law attorney Peter Tompa feels that the repatriation is merely the latest in a cynical attempt by the Italian government to reacquire its lost artifacts, as opposed to any concerted effort to reclaim actual stolen property. [fn15] Tompa also indicts Italy for having what he calls an guilty until proven innocent mentality, and references a quote from The New York Times which states that Italy “. . . the general assumption is that someone is guilty until proven innocent. Trials — in the press and in the courts — are more often about defending personal honor than establishing facts, which are easily manipulated.”[fn16]

But let’s compare this to the Kingsland saga. On the one hand, a valuable collection of art – the majority of which has been positively identified as having been reported stolen at some point in the past – has the likelihood of never being returned to its proper owners; instead, it could very well end up on the auction block at some point in the future, where distant relations of the possible thief will stand to make a healthy profit from the auction of the purloined goods.

On the other hand, we have an extensive collection of possibly stolen / possibly legally purchased goods, of similarly questionable provenance, all of which can be tied to the nation of Italy and of great historical importance for the country, which have been returned at the bequest of the of inheritor of the goods, facilitated by the US government, to their (arguably) rightful home.

Which scenario seems more ethical? It is difficult to make an argument which favors the heirs of the Kingsland collection; should a completely disinterested group of relatives be allowed to profit from possibly criminal activity? True, there is no single entity like a country claiming rightful ownership of Kingsland’s art; but does that mean that simply because no one at all is stepping forward to claim it that it should be open season on it?

The heirs of Kingsland/Kohn would be well-advised to consider the importance to art as an essential part of our cultural landscape and to take an approach similar – though not identical – to that taken by Joseph Sisto. Like the natural resources which make up our environment, the art of the past is an important and dwindling cultural resource, one which needs to be properly nurtured and tended in order to thrive. When it is treated as mere common chattel, of no greater significance than an old family dresser, all suffer.

It is both unfathomable and unfortunate that Kingsland had such disregard – intentionally or otherwise – for the importance of maintaining the provenance of art. Let us hope that, whatever eventually becomes of the Kingsland collection, that it won’t be hoarded like it was by Kingsland himself, and that the future owners / possessors / proprietors treat it not as mere objects to be owned and disposed of at will, but as precious artifacts to be cherished, appreciated, and then passed on to the next generation, in a sound manner of succession which respects both the integrity of the art itself and the culture to which it belongs.

FOOTNOTES

[fn1] Marsh, George Perkins. The Earth as Modified by Human Action: Man and Nature (1874) [emphasis added]

[fn2] Ibid.

[fn3] Konigsberg, Eric. “Two Years Later, the F.B.I. Still Seeks the Owners of a Trove of Artworks” The New York Times, August 11, 2008

[fn4] Shapiro, Gary. “William Kingsland, City ‘Gazetteer,’ Is Dead” The New York Sun, April 13, 2006

[fn5] Konigsberg, Eric. “Two Years Later, the F.B.I. Still Seeks the Owners of a Trove of Artworks” The New York Times, August 11, 2008

[fn6] Shapiro, Gary. “William Kingsland, City ‘Gazetteer,’ Is Dead” The New York Sun, April 13, 2006

[fn7] Konigsberg, Eric. “Two Years Later, the F.B.I. Still Seeks the Owners of a Trove of Artworks” The New York Times, August 11, 2008

[fn8] Ibid.

[fn9] Shapiro, Gary. “Genealogists Discover Identity of Enigmatic Upper East Side Collector” The New York Sun, December 14, 2006

[fn10] Ibid.

[fn11] Ramirez, Margaret and Mitchum, Robert. “1,600 antiquities for Italy: FBI sending back stolen artifacts found in Berwyn” Chicago Tribune, June 9 2009

[fn12] “Stolen Cultural Artifacts Found in Berwyn Residence Returned to Italian Authorities” June 8 2009, F.B.I. Press Release http://chicago.fbi.gov/pressrel/2009/cg060809.htm

[fn13] “Son ‘Relieved’ To Tell Cops Of Dad’s Stolen Artifacts” June 10, 2009, http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=105218287

[fn14] Tompa, Peter. “The Strange Case of the Sisto Collection” June 9 2009, http://culturalpropertyobserver.blogspot.com/2009/06/strange-case-of-sisto-collection.html

[fn15] Ibid.

[fn16] Donadio, Rachel. “In Italy, Questions Are From Enemies, and That’s That” The New York Times, June 6, 2009,

WORKS REFERENCED BUT NOT CITED

Alter, Denise M., Esq. “Should Collectors Worry about Art Theft? The Importance of Provenance and Good Title” http://artelligenz.com/2007/04/12/should-collectors-worry-about-art-theft/

Seminar Paper: The Google Books Settlement Agreement

I’m publishing here a series of papers written by law students in my ‘Property, Heritage and the Arts’ seminar from the Fall of 2009. This paper was written by Matthew Detiveaux:

A New Rubric for Cultural Heritage Management and Privatization?

With the digital age now at its heyday, everything changes. When we want to know something about a topic, we Google or Wikipedia it. When we want to see what something looks like, we perform an image search. When we want to hear an artist, we “download” them. When we want to read a book, Google hopes that we will use Google Books to find it, preview it, and gain access to it.

Using complicated algorithms similar to those used to fuel what is arguably the world’s most sophisticated web browser, Google has unveiled Google Books[i]. Like Google’s other services, Google Books provides a simple, intuitive interface built around the user’s needs. Google has made its name on being the web browser of choice for just about everyone. Many turn to Google for e-mail (Gmail[ii]), driving directions (Google Maps[iii]), news (Google News[iv]), social interaction (Orkut[v]), streaming video (YouTube[vi]), and even cell phone service (the T-Mobile G1, powered by a Google Operating System[vii]). Google’s new hat is not only that of a librarian; Google wants to be the largest, most comprehensive digital library in the world. This is right in accord with Google’s mission: “to organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful.”[viii]

Google, Inc. was founded in 1998 by Larry Page and Sergey Brin, two Stanford Ph.D. candidates who developed algorithms to “data mine” the far reaches of the Internet and bring the most relevant and useful pages forward in a search tool.[ix] The patented PageRank[x] search formulas are highly complicated, with more than 500 million variables and 2 billion terms being used to run its search engine in 1999 alone. Not so confusing are the economics. On January 22, 2009, Google announced fourth quarter financial revenues of $5.7 billion, an 18% increase, when compared to 2007 fourth quarter earnings.[xi] Google, repeatedly voted one of the best places to work in America, is a household name and a Goliath when it comes to the Internet.

“In the beginning, there was Google Books”.[xii]

“About Google Books” tells the story of two Stanford Ph.D. students who had the dream of a “future world in which vast collections of books are digitized,” and “[where] people would use a ‘web crawler’ to index the books’ content and analyze the connections between them, determining any given book’s relevance and usefulness by tracking the number and quality of citations from other books.”[xiii] These two doctoral students were Larry Page and Sergey Brin, the co-founders of Google. Citing the inspiration of other digitizing projects, the two formed a team of “Googlers” who worked hard to make their dream a reality. They visited libraries, universities, and publishing companies to clarify their vision. While visiting the Bodleian library at Oxford University, they mused: “For the first time since Shakespeare was a working playwright, the dream of exponentially expanding the small circle of literary scholars with access to these books seems within reach.”[xiv] These Googlers are not just dreamers, they are negotiation experts. In 2004, “Google Print” was joined by Blackwell, Cambridge University Press, The University of Chicago Press, Haughton Mifflin, Hyperion, McGraw-Hill, Oxford University Press, Pearson, Penguin, Perseus, Princeton University Press, and more.[xv] Later that same year, the Google Library Project partnered with Harvard, the University of Michigan, the New York Public Library, Oxford, and Stanford. Today, Columbia, Cornell, University of Texas and others have joined the Google Library Project, an arm of Google Books. [xvi]

A Harvest in Need of Laborers

Cultural property is traditionally thought of as objects or art that belong to a group of people or those who share a cultural identity. With the Internet and technological advances expediting the process, knowledge, commerce, and even culture have gone global. With few restrictions, the world is quite literally at one’s fingertips. It is of no surprise that purveyors of cultural property – museums, libraries, and archives – are seeking out ways to use the technology and the Internet to accomplish their missions.[xvii]

There are predominately broad category of things being preserved by museums, archives, and libraries today. First are the traditional, pre-digital things. Such include: graphic arts, sculpture, books, governmental documents, and pretty much anything that was not created and simultaneously published using computers and the Internet. The second category contains the rest, that with which we interact on a daily basis: everything that was “born digital”. The mission of the Internet Archive is to preserve the second class of information; they are trying to preserve the Internet, itself, as a cultural artifact.[xviii]

In mid-2008, Google hit a milestone when its Internet tracking software counted and databased 1 trillion unique uniform resource locators, or URLs (websites) on the web.[xix] Internet Archive, founded in 1996, had goals of archiving all this information, literally keeping the files accessible for future generations to browse.[xx] Problematic to Internet Archive’s goal today is that the web is so big due to the easy of website creation and ubiquity of users. Additionally the Archive requires the skill of a programmer to use the site.[xxi] So, although Archive suggests that we have a “Right to Remember” our digital cultural property, that right comes with the obligation to know more than how to turn on a computer and functionally surf the web.

Regarding digital preservation, question remains open as to what should be preserved. Archive is the only visible organization out there with the primary goal of preserving the web experience, itself, for future generations.[xxii] Quite fun is using the “Way Back” machine to access old Geocities sites.[xxiii] Archive claims there is social value in knowing what people were doing online at any given moment in the Internet’s history. But, because the Internet is the sum of all computers connected to it and the input of all users at those computers, the Internet is an intrinsically dynamic and ever-changing thing.[xxiv] Since not all the computing power of the machines connected to the Internet will ever be dedicated to preserving a history of the different interactions of these machines, there will never be a computer (or network) able to document the most ever-changing system known to man. Even if we choose to preserve a certain feature or niche of the Internet, other presumptions must be taken on. For instance, does e-Bay tell us more about commerce than people’s stock research? The Internet Archive raises many fundamental questions of digital cultural heritage left unanswered: if the Internet is an accumulation of all its users, who and what is worth preserving?

Other preservation projects focus on preserving “pre-digital” or digitally independent works. These works include, but are not limited to, books, movies, art, photography, and documents.[xxv] Libraries and museums have struggled to “digitize” their collections for preservation and Internet publication for two specific reasons: money and law.[xxvi]

Because digitization is so new a phenomenon and so specific to what is being digitized, no one can say exactly what needs to be done. For example, where museum preservation techniques for a Venetian vase are pretty well established, no one is quite certain how to preserve a digital picture of that vase so that future generations can view it; intricate problems arise with the ever-changing types of media used to record our arts and humanities.[xxvii] Beginning in April of 2009, the University of Leicester School of Museum Studies opened a MA/MSc program specifically for digital heritage.[xxviii] Under the course details, it touts itself as “at the centre of, and helping to shape an emerging discipline – one of only a few courses which locate themselves specifically at the nexus of digital media and heritage.”[xxix]

But, the digital heritage discussion is not just for academics. In 2000, Congress appropriated $100 million to create the National Digital Information Infrastructure and Preservation Program (NDIIP), an organization whose mission is to save things “born digital”.[xxx] However, the program had $47 million of its funding rescinded and is threatened by not receiving matching non-governmental funding. Already lost and gone are raw data from early satellite probes, including the Viking mission to mars, websites covering federal elections, and other data sources covering natural disasters like Hurricane Katrina.[xxxi] In the digital age, the Internet is not only our source for news; it is our newspaper. Because of its dynamic, fundamental quality, the question remains: “Which data should we keep and how should we keep it? How can we ensure that we can access it in five years, 100 years or 1,000 years? And, who will pay for it?”[xxxii]

As usual, the problem of money and law do not operate on separate planes; instead, they are closely inter-related. Museums face various problems when going to digitize their works, mostly in the face of copyright law. “The interface of digital cultural preservation and copyright law confronts museums with challenges that are much more salient and crucial for the continuous cultural vitality of museums and their presence in digital domains.”[xxxiii] Aside from a concerted lack of consensus on whether to digitize, how to digitize, and how to fund digitizing, museums that have affirmatively answered these questions run into the issues of law. Copyright and licensing have been the key legal players in this realm.[xxxiv]

The Librarian of Congress issued a group to study the effects of Section 108 of the Copyright Act, the Fair Use Doctrine, on museum digitization efforts and to promulgate legislative suggestions to solve these problems.[xxxv] Traditionally, one major problem museums face is that museums are not even eligible under the Fair Use Doctrine of Section 108(b) of the Copyright act.[xxxvi] Further, the Act limits those who do fall under it to three copies of a work, and does not provide for digital copies for preservation efforts.[xxxvii] Most importantly, as Pessach notes, current Section 108 does not cover the provision of on-line, public access to digitally preserved materials[xxxviii]. Thus, museums wishing to digitize cannot forecast the legality of doing so. To date, courts have not had the opportunity to review the use of the Fair Use Doctrine regarding museums’ use and distribution of digital copies of their works.[xxxix] But, arguably, the courts have answered this question for a company called Google.

Pessach cites the famous Arriba Soft case (280 F.3d at 944) and Perfect 10, Inc. v. Google, Inc., 416 Supp 2d 828 (C.D. Cal. 2006) in drawing a distinction between the societal roles of search engines and museums. “Search engines provide commercial functions that are different from the unique functions that cultural institutions may require.”[xl] Legal problems may arise when museums digitize works of art. American courts hold that works produced by digitization are not subject to their own copyright; thus, the underlying copyright of a work being digitized is the copyright that applies to the original work. Therefore, museums’ ability to digitally display any work they might digitize becomes a question of copyright infringement.[xli] In contrast, British law provides that the digitized (photo) is subject to a new copyright.[xlii] The British approach differentiates an “original” from a “new work”, based on a minimal standard of labor and skill used to create the new work.[xliii] Pessach concludes that fair use law should be liberally applied to museums.[xliv] Museums’ role, as public trusts and the purveyors of cultural knowledge and cultural heritage, necessarily conflicts with the underlying rule of copyright, that markets are the appropriate arena for producing and distributing cultural goods.[xlv][xlvi] This battle is not simply theoretical or academic, but is pertinent in the Google Books case being litigated in the courts today.

The Lawsuit

On December 1, 2009, the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York filed a Memorandum Decision against plaintiff Amazon.com, as a member of the plaintiff class, against reconsidering the granting of “the Court’s order granting preliminary approval of the parties’ Amended Settlement Agreement.”[xlvii] Prior to this decree, on November 19, 2009, the Court granted preliminary approval of the Amended Settlement.[xlviii]

The Google Books Settlement Agreement is the result of about five years of litigation, starting in 2004, when Google announced that with its Library Project, it would begin scanning the entire contents of the libraries of Harvard, the University of Michigan, the New York Public Library, Oxford, and Stanford. The combined collections are estimated to exceed 15 million volumes.[xlix] The suit was brought by the Authors’ Guild and McGraw-Hill Cos, Inc., to enjoin Google from scanning their books and publishing them on the Internet. Under the Settlement Agreement, Google will pay $125 million to authors and publishers, including $45 million to copyright holders whose works were digitized without permission.[l] Google will also create a Book Registry, which will be the clearinghouse for the funds raised through its Google Books services. Authors of “orphaned” works, those Google has determined have been abandoned or are without traceable proprietary rights, will have five years from the day that revenues are created by that book to come forward and claim their portion the revenues. Otherwise, those revenues will become part of the Book Registry and be used to facilitate its operation. As far as those who have already had their books scanned by Google, they have the following options. They can opt out of the Google Books program, requiring Google to remove their book from its system. They can opt out of the Google Books lawsuit, allowing them to be removed from the “member class” and gain the ability to bring their own suit against Google Books, or they can do nothing.[li]

Monday, December 14, 2009, the Federalist Society of New York hosted a public debate regarding the legal issues surrounding Google Books. The debate was led by the infamous contracts scholar, Richard A. Epstein and Jonathan Jacobson, a partner at Wilson Sonsini Goorich & Rosati. Epstein argued against the book deal, while Jacobson argued for it.[lii] Jacobson: “We must stand up and applaud [Google], because this really is the new Library of Alexandria.”[liii]

During the Federalist society debate, one woman repeatedly interjected her ideas on the matter. Her name is Lynn Chu, and she is a lawyer, a journalist, and the literary agent of David Brooks, Richard Epstein, Ken Star, Clarence Thomas, and others.[liv][lv] Quite pertinently, the rhetorical question was addressed to the audience as to why an author wouldn’t come forward and claim the profits gained from Google’s making his book available online. Chu responded, simply, that copyright law has never before made authors do such a thing to reap the benefit of their profits.[lvi]

The legal questions surrounding the Settlement are profound and legion. First, there is the issue of whether this Settlement agreement is not really an agreement at all, but whether it is creating a novel legal right to be given to a private entity. Epstein argued (alongside the Department of Justice) that it would have been much simpler to have an “opt-in” scheme as opposed to an opt-out scheme.[lvii] In that way, authors, publishers, and those with intellectual rights in books can choose to be a part of the program instead of being defaultly included in the program and having to elect to be not so.[lviii] The Settlement Agreement leaves unanswered questions of what Google can and will do with the Books, and the program has already made preparations for Google to sell advertising space within the books it creates. The counter to this argument is that without the opt-out format, Google will have no way of protecting and including “orphaned” books, whose societal value would otherwise be lost if was not part of the Google Books repository and made available to the Internet.

The Department of Justice was, at the time of this paper, investigating the Settlement Agreement, but to the author’s knowledge, nothing beyond a memorandum in the interest of the United States of America and against the Settlement Agreement was filed.[lix] The DOJ memorandum only mentions the potential for Google Books becoming a monopoly, in opposition of anti-trust law in force. The Memorandum specifically mentions that Google might, by virtue of being the only entity with the digital copies of these orphaned works, create a service unto itself that, via the Book Registry, would be unassailable to competition. Further, since under the Agreement, Google would be able to act “only to the extent permitted by law,” the question remains open as to whether or not future other corporate entities could gain licenses from Google to use the books, since it is unclear where the copyrights of those scannings is vested, in Google or in the original author of the book.[lx]

The DOJ Memorandum also cites that the issue of this being a class action suit is questionable, because it may not afford sufficient notice to all members involved. “The Proposed Settlement is one of the most far-reaching class action settlements of which the United States is aware; it should be no surprise that the parties did not anticipate all the difficult legal issues such an ambitious undertaking might raise.”[lxi] Further, the DOJ muses whether or not the Agreement effectively settles in favor of all those plaintiffs purportedly represented, because, with its gaps, it does not specifically say what can and can’t happen in the future to those works of authors.[lxii]

More globally, the DOJ memorandum cites policy concerns. “As a threshold matter, the central difficulty that the Proposed Settlement seeks to overcome – the inaccessibility of many works due to the lack of clarity about copyright ownership and copyright status- is a matter of public, not merely private, concern.”[lxiii] Finally, the DOJ forecasts problems with the potential of the Agreement to overbroadly sweep in foreign works, whose authors are not required to register under U.S. current copyright law.[lxiv]

Private Interests versus Public Gain

The profound thing about Google Books is that it is assumes the role of a public trust while maintaining its identity as a private, for-profit, company. The Google Books settlement agreement answers for a private, for-profit entity what no court has answered for the non-profit museums wishing to digitize: whether it is legal to take the tangible work of a living person, digitize it, and make it available to the public. Under the terms of the agreement, Google will retain more than thirty percent of the sales of the digitized copies of the books.[lxv] Additionally, Google will profit from advertisements within the Google Books search page, the referral to external bookstores for the purchase of a given book, and the in-line advertisements in the digital books, themselves. To date, Museums have no such law as the Google Books Settlement Agreement to protect them from known and unknown copyright holders. Being exempt from Section 108(b), the Fair use Doctrine, museums are left out in the cold.

In an early 2009 article, Michael Dunn argued that the question of fair use regarding the Google Books settlement has been intentionally side-stepped by Google and the court.[lxvi] “In reaching the settlement, the parties dodged the question of whether the digitization of a book, in whole or in part, would qualify as protected fair use. Although Google has answered the question for itself, the question remains for other digitizers.”[lxvii] These other digitizers include museums, whose traditional role has been to be the guardians of culture, art, and knowledge. What we are seeing in the Google Books case is the privatization of the role of Cultural Guardian, a role usually reserved to museums, public libraries, and the state. As the Department of Justice points out, the litigation-based agreement is vastly sweeping, so much so that it vests Google indefinitely with a privilege and a duty highly coveted: being the biggest and best library in the world.

Although the Google website touts partnerships with authors and printers, the Department of Justice’s concerns about the sweeping effects upon international literary copyright have become a reality. In a decision December 19, 2009, the French court demanded that Google stop scanning the French books cited in a pending court case and pay 300,000 in damages and interests to publishers.[lxviii] Google Books France’s attorney Alexandra Neri responded: “I don’t think anyone wins. This decision just holds back the progress of access to online information. Defense of author’s rights are a French tradition, but now France could be left behind, without access to its own culture.”[lxix] The court mandated that this be published on Google’s French “Google Books France” website, along as be published in three newspapers.[lxx]

There is also upheaval in China. Mian Mian has filed a lawsuit against Google, claiming copyright infringement regarding her book “Acid Lover”.[lxxi] Although Google deleted the work from its website, the work still appears in searches. Ms. Mian is seeking Google to remove all passages of her book and issue her a public apology, along with damages to the tune of about $8,800. She is the first individual writer in China to sue Google China.[lxxii]

Final Thoughts

Surely, Google is a good candidate for the scanning of libraries’ books; it is one of the most technologically-advanced companies in the world, and it has the funding to make librarians’ dreams come true. Aside from the murky legalities and angry publicists, Google Books has become a success, and Google is proud to have prevailed in its quest.

“Today we’re delighted to announce that we’ve settled that lawsuit and will be working closely with these industry partners to bring even more of the world’s books online. Together we’ll accomplish far more than any of us could have individually, to the enduring benefit of authors, publishers, researchers and readers alike.”[lxxiii]

Quite relevant is Google’s next digitization project, the Iraqi museum.[lxxiv] For this announcement and ceremony, not only did the CEO visit, he brought his daughter, journalists, bodyguards, and American embassy officials. In a public address, he said: “I can think of no better use of our time and our resources than to make the images and ideas from your civilization, from the very beginnings of time, available to billions of people worldwide.”[lxxv] U.S. Ambassador Christopher R. Hill touted the event as a good thing, being “part of an effort spearheaded by the State Department to bring technology to Iraq. We thought, what better way to do that than to bring Eric Schmidt to Iraq?” Another State Department official refuted the suggestion that event was a government-sponsored infomercial, citing that other companies are involved.[lxxvi]

Curiously, Iraqi citizens were not invited to the event. The museum has been closed since the beginning of the Iraq occupation by American troops, although three intermittent partial openings have taken place over the course of the American stay. Most of the museums’ treasures are still hidden from the public eye in secret storage, due to strings of lootings that have taken place since the American occupation.

At the same time, Nicholas Sarkozy has unveiled a 35 billion spending plan, geared toward digitizing French documents and preparing France for the “challenges of the future”.[lxxvii] Back home, the Library of Congress’s National Digital Information Infrastructure & Preservation Program moves along at an unknown pace, while Google and its lawyers fight vigorously for the right to become the new, universal library and potentially, the new museum.

In “Trade Versus Culture in the Digital Environment: An Old Conflict in Need of a New Definition”, Mira Burri-Nenova discusses the UNESCO Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions, its presumption that culture is distinct from trade, and the impact this assumption will have in the law’s inefficacy in respect to WTO agreements.[lxxviii] As she points out, “…cultural rights do not correspond to national boundaries”.[lxxix] “It is indeed odd that while the convention clearly acknowledges the dual (trade and culture) nature of cultural goods and services and celebrates their cultural side, no attempt is made to provide guidance on how states might reduce the trade distorting effects of cultural policy matters.[lxxx]

As the Department of Justice quite clearly stated in its brief for the Google Books case, the threshold issue is one of public policy.[lxxxi] That policy regards cultural property and the question of whose it is. Is an accumulation of the world’s books, legally and morally, ours for the taking? And if so, is it responsible to give the books, the library itself, and the keys to the building to a private company? The Google Books case exemplifies what the heart of Burri-Nenova’s argument: culture and trade are intrinsically and fundamentally intertwined, and international policy that does not fully acknowledge both, as inter-dependent, is inherently flawed. She writes,

“…[I]t is likely that most of the existent and conventionally applied cultural policy measures, which are only ‘analogue-based’, do not sufficiently take into account the changed regulatory environment, nor do they have the potency to address appropriately the new digital conditions. If such measures are maintained, we hold that they serve either protectionist interests or are the remnants of an ill-conceived (but politically accepted) perception of globalization and its effects upon culture.”

(Burri-Nenova, 40, 41) (emphasis added).

Google’s mission, “to organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful,” is an ambitious one to say the least. As opposed to the case of pictures[lxxxii] the goal of organizing the world’s books demands that Google take those books and digitize them as its primary step. As is clear, the legal implications of this are profoundly vague and worrisome, not only to authors and publishers, but also to any of us that have copyright interests of anything, including art other intellectual property. Could the next step be a patent search engine, using complex algorithms to link patents with similar components together? Whether we have a “Right to Know” and a “Right to Remember” beg a huge underlying question which Google has not answered or even acknowledged, does Google have the right to organize our world and sell it back to us?

“Finally, one should bear in mind that the new information environment is extremely dynamic and complex and exacerbated the interrelatedness of effects, making regulatory decisions precarious.”[lxxxiii] If not overturned, this court decision will have groundbreaking effects, not only on writers, publishers, and literary agents, but it potentially spur new law relevant to other private digitization ventures like the Google Iraq Museum venture. On one hand, it may either provide a breakthrough in some museums’ efforts to digitize, breaking copyright barriers rights open. But on the other, it may advance other multi-national corporations to key positions, allowing them ripe, unbridled access to unknown lodes of cultural property, the likes of which are owned by the Iraq museum. In this brave new chapter in preservation history, will the Google Books Settlement Agreement become a standard for privatization of cultural property stewardship? As of today, the Agreement is provisionally in effect and has not been appealed. We can only speculate as to what it will mean to the arts, humanities, and academic communities outside the literary sphere, especially to our museums.

________________________________

[i] http://books.google.com/intl/en/googlebooks/about.html

[ii] http://mail.google.com/

[iii] http://maps.google.com/

[iv] http://news.google.com/

[v] http://www.orkut.com/

[vi] http://www.youtube.com/

[vii] http://www.t-mobileg1.com/

[viii] www.google.com/corporate/facts.html

[ix] http://preg.org/collectibles/mentalplex.cmon/presskit/GoogleCorp.pdf

[x] http://www.google.com/corporate/tech.html

[xi] http://investor.google.com/releases/2008Q4_google_earnings.html

[xii] http://books.google/com/intl/en/googlebooks/history.html

[xiii] Id.

[xiv] Id.

[xv] Id.

[xvi] See http://googleblog.blogspot.com/2005/10/point-of-google-print.html.

[xvii] Carey Stumm, Preservation of Electronic Media in Libraries, Museums, and Archives, The Moving Image, Vol. 4, No. 2, 39 (2004).

[xviii] “About the Internet Archive”, http://www.archive.org/about/about.php

[xix] “We knew the web was big…”, http://googleblog.blogspot.com/2008/07/we-knew-web-was-big.html

[xx] “About the Internet Archive” at ¶4.

[xxi] Id. at ¶8.

[xxii] While Google does archive web pages, it does not have a distinct mission or commitment to this function.

[xxiii] Available at http://www.archive.org/web/web.php.

[xxiv] See generally Mira Burri-Nenova, Trade Versus Culture in the Digital Environment: And Old Conflict in Need of a New Definition, 12 J. Int’l Economic Law 17 (2009) and Guy Pessach, [Networked] Memory Institutions: Social Remembering, Privatization and Its Discontents, 26 Cardozo Arts & Ent. L.J. 71 (2008).

[xxv] See Stumm, 40.

[xxvi] Guy Pessach, Museums, Digitization and Copyright Law: Taking Stock and Looking Ahead, 1 J. Int’l Media & Ent. L. 253, 257 (2006).

[xxvii] Stumm, 40.

[xxviii] http://le.ac.uk/ms/study/digitalheritage.html

[xxix] Id.

[xxx] Jim Barksdale and Francine Berman, “Saving Our Digital Heritage”, The Washington Post. May 16, 2007. Available at: http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/05/15/AR2007051501873.html.

[xxxi] Id.

[xxxii] Id.

[xxxiii] Pessach: Museums, 256.

[xxxiv] Id.

[xxxv] http://www.section108.gov

[xxxvi] The Section 108 Study Group, The Section 108 Study Group Report (2007), http://www.section108.gov/docs/Sec108StudyGroupReport.pdf, ii, iii.

[xxxvii] Id. at v.

[xxxviii] Pessach: Museums, 267.

[xxxix] Id. at 272.

[xl] Id. at 274

[xli] The Bridgeman Art Library, Ltd. v. Corel Corp., 36 F. Supp 2d 191 (S.D.N.Y. 1999).

[xlii] See Antiquesportfolio.com Plc. Rodney Fitch & Co. Ltd., [2001] FSR 23.

[xliii] Pessach, FN88.

[xliv] Id. at 281.

[xlv] Id. at 28.

[xlvi] See also Pessach: [Networked] Memory Institutions. cited above.

[xlvii] The Authors Guild, Inc., et al. v. Google Inc., Case No. 05 CV 8136 (S.D.N.Y.).

[xlviii] Id.

[xlix] http://books.google.com/intl/en/googlebooks/history.html

[l] Michael Dunn, The Google Digitization Settlement: The Fair Use Question Remains, martindalehubble.com, http://www.martindale.com/internet-law/article_Sheppard-Mullin-Richter-Hampton-LLP580998.htm, Accessed on December 21, 2009.

[li] Andrew Nusca, Google Books search settlement: monopoly or public service?, http://blogs.zdnet.com/BTL/?p=28517&tag=conent;col1.

[lii] Id.

[liii] Id.

[liv] David Lat, The Google Books Settlement, http://abovethelaw.com/2009/12/the_google_books_settlement.php

[lv] See Also Lynn Chu, “Google’s Book Settlement is a Ripoff for Writers”, The Wall Street Journal Online, Michael Dunn, The Google Digitization Settlement: The Fair Use Question Remains, martindalehubble.com, http://www.martindale.com/internet-law/article_Sheppard-Mullin-Richter-Hampton-LLP580998.htm.

[lvi] Lat, at ¶12.

[lvii] Id. at 5.

[lviii] Statement of Interest of the unites States of America Regarding Proposed Class Settlement, filed 09/18/2009. Available at: http://www.justice.gov/atr/cases/f250100/250180.pdf.

[lix] Id.

[lx] Id. at 23.

[lxi] Id. at 1.

[lxii] Id. at 5, 8.

[lxiii] Id. at 2.

[lxiv] Id. at 11.

[lxv] Dun at ¶3.

[lxvi] Id. at ¶5.

[lxvii] Id.

[lxviii] Mercedez Bunz, “Google fined for digitising French books”, guardian.co.uk, http://www.guardian.co.uk/media/2009/dec/18/google-books-french-court.

[lxix] Gaelle Faure, “French court shuts down Google Books project”, The Las Angeles Times, http://www.latimes.com/news/nation-and-world/la-fg-france-google19-2009dec19,0,548537.story.

[lxx] Id.

[lxxi] Edward Wong, “Chinese Writer Sues Google China”, The New York Times – World Briefing, http://www.nytimes.com/2009/12/17/world/asia/17briefs-google.html.

[lxxii] Id.

[lxxiii] http://books.google.com/googlebooks/agreement/

[lxxiv] “Google to digitize artefacts at Iraq National Museum”, BBC, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/middle_east/8376554.stm.

[lxxv] Id.

[lxxvi] Id.

[lxxvii] “Google fined…” guardian.co.uk, at ¶8.

[lxxviii] Mira Burri-Nenova, Trade Versus Culture in the Digital Environment: And Old Conflict in Need of a New Definition, 12 J. Int’l Economic Law 17 (2009)

[lxxix] Id. at 25.

[lxxx] Id. at 28.

[lxxxi] Statement of Interest, 2.

[lxxxii] See Perfect 10, Inc. v. Google, Inc., 416 Supp 2d 828 (C.D. Cal. 2006)

[lxxxiii] Burri-Nenova, at 62.

Recreating Strawberry Hill

Strawberry Hill, the gothic-revival mansion in west London is currently in the midst of a £9m restoration. Martin Bailey has a terrific story in the Art Newspaper on the efforts to track down many of the objects which were originally included in the mansion.

Strawberry Hill, the gothic-revival mansion in west London is currently in the midst of a £9m restoration. Martin Bailey has a terrific story in the Art Newspaper on the efforts to track down many of the objects which were originally included in the mansion.

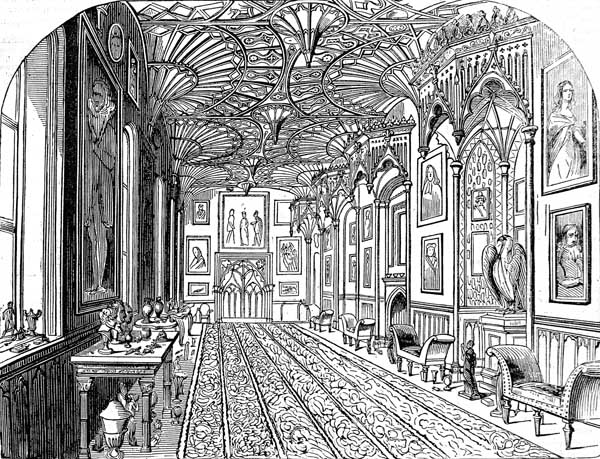

Horace Walpole built the home in the 18th century, which is credited for the revival of the Gothic style in Victorian England. The building was inspired by the fan vaulting at Westminster Abbey, bits of tombs from Westminster and Canterbury, and the tomb of Edward the Confessor. When Walpole died in 1797, most of the objects remained at the mansion, but an auction in 1842 led to the loss of a number of the objects. The Strawberry Hill Trust is now eager to bring these objects back together, including paintings, sculpture, furniture, ceramics, glassware, weapons, relics and manuscripts.

Some of the most sought-after items include:

1. A Roman funerary urn: The Roman urn appears below the window in a 1750s drawing of Walpole in his library by Johann Müntz. Its triangular top decoration has a tripod relief, supported by griffins.2. Mirror with portrait of Viscount Malpas: There were two mirrors, and the lost mirror has a circular painting of Viscount Malpas. The Gothic mirror, with an ebonised wood frame, was sold in 1842 to Mrs Dawson Damer. Another mirror depicting the Earl of Orford survives (pictured, it was accepted in lieu of inheritance tax last year and will be displayed at Strawberry Hill).3. Ornate Turkish dagger: The ornate dagger was reputed to have belonged to Henry VIII. In 1842 it was bought by actor Charles Kean, who is said to have used it on the stage. It was sold at Christie’s in 1898 to someone named as Haigham. It is depicted in a late 18th-century watercolour.4. Gothic dining table Commissioned by Walpole in 1754, the top is of Sicilian jasper (6 x 3 feet), with the frame in black. An early 19th-century drawing of it survives. The ornately decorated table was last recorded in 1953, when it was owned by antiquarian Harry Bradfer-Lawrence, of Ripon, Yorkshire, who died in 1965.5. Basalt Bust of Vespasian: The colossal basalt bust had been in 10 Downing Street and was later put on display at Strawberry Hill. It is depicted in a watercolour view of Horace Walpole’s gallery. The bust was last recorded at Christie’s in 1893, after leaving the Hamilton Palace collection.

- Martin Bailey, Strawberry Hill on the hunt for lost Walpole treasures, The Art Newspaper, January 6, 2010.

The Year in Cultural Policy

2009 saw a number of interesting trends in cultural heritage law and policy. Below are a few of the year’s prominent stories. On a personal note, I am still enjoying the fellowship at Loyola in New Orleans; but still looking for a permanent position that will allow me to continue writing and thinking about cultural heritage. But in the mean time your interest and support continues to enrich and support my work. There is a need for people to continue thinking and writing about culture. The blog saw a lot of interest this year, with nearly 80,000 visitors. I’d like to thank you all for your interest, comments, and helpful notes and conversations.

The Four Corners Antiquities Investigation A large federal investigation into the illegal trade in Native American Artifacts signaled a growing commitment of federal authorities into policing Native American artifacts. A June 10th raid which searched the homes and businesses of over 20 people lead to arrests, and even two suicides. So far charges have emerged in Utah, but charges may emerge in New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada, and perhaps even Colorado.

A large federal investigation into the illegal trade in Native American Artifacts signaled a growing commitment of federal authorities into policing Native American artifacts. A June 10th raid which searched the homes and businesses of over 20 people lead to arrests, and even two suicides. So far charges have emerged in Utah, but charges may emerge in New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada, and perhaps even Colorado.

Ongoing Repatriation Efforts

Deaccession

The decision by museums to sell works of art generated considerable controversy this year, and no dispute better encapsulates the difficulties which arise than the decision by Brandeis University to close the Rose Museum of Art. The University has shifted its position since the initial announcement. It has announced its intention to maintain the Rose in some form, but given the University’s financial difficulty the decision was not made lightly. One of the difficulties with deaccession stems from its connection to our fundamental view of art and museum governance. What is the nature of art? An art museum? Are either permanent? Can we trust the governing structures in our museums? Our inability to find common ground in crafting answers to these questions accounts for the continued difficulty. But if the arts community cannot come together and craft viable solutions to these difficulties, we are going to be left with weaker cultural institutions and risk losing more works as a result of financial difficulty.

The decision by museums to sell works of art generated considerable controversy this year, and no dispute better encapsulates the difficulties which arise than the decision by Brandeis University to close the Rose Museum of Art. The University has shifted its position since the initial announcement. It has announced its intention to maintain the Rose in some form, but given the University’s financial difficulty the decision was not made lightly. One of the difficulties with deaccession stems from its connection to our fundamental view of art and museum governance. What is the nature of art? An art museum? Are either permanent? Can we trust the governing structures in our museums? Our inability to find common ground in crafting answers to these questions accounts for the continued difficulty. But if the arts community cannot come together and craft viable solutions to these difficulties, we are going to be left with weaker cultural institutions and risk losing more works as a result of financial difficulty.

Treasure Seekers in the United Kingdom

Earlier this year Oxford Archaeology released a report on the management of undiscovered antiquities in England and Wales. The conclusion? Illegal metal detecting in England has declined since the United Kingdom amended the Treasure Act and created the Portable Antiquities Scheme. This has led to the amateur discovery of some beautiful objects, including this Anglo-Saxon hoard discovered by a detectorist this summer.

And of course art theft continued to occur with alarming regularity.

Katt on the Importance of Archaeological Context

Light Posting

Apologies for the light posting of late, I hope to resume early next week. I’ve been finalizing my preparations for the AALS Hiring Conference in Washington DC this weekend. Joni will be joining me as well, and if any readers or former students are up for dinner or drinks, drop me a line: derek.fincham “at” gmail.com.

Apologies for the light posting of late, I hope to resume early next week. I’ve been finalizing my preparations for the AALS Hiring Conference in Washington DC this weekend. Joni will be joining me as well, and if any readers or former students are up for dinner or drinks, drop me a line: derek.fincham “at” gmail.com.

No Libraries in Philadelphia?

We get the State and City we deserve. Another sign of the dismal state of liberal arts funding generally. If the Pennsylvania State Legislature doesn’t allocate funds, the Philadelphia Free Library will close on October 2nd and end all programs and services. All books are due on October 1st.

The Pennsylvania senate is unable to pass a budget, and this late-arriving state funding will force the closure of the entire system. Perhaps a Pirate Party can fill the void for the citizens of Philadelphia to get access to books, movies and music.

All Free Library of Philadelphia Branch, Regional and Central Libraries Closed Effective Close of Business October 2, 2009 [Free Library of Philadelphia]

Early Review of the Art of the Steal

The Art of the Steal is a new documentary on the Barnes foundation and its planned move from Merion. Scott Tobias has a review for the AV Club:

As a forward-thinking art collector in the ‘20s, Dr. Albert Barnes snapped up an extraordinary wealth of post-impressionist and modernist paintings from the likes of Matisse, Picasso, Renoir, and Cezanne; though dismissed by tastemakers at the time, his collection is now valued in the tens of billions. In his will, Dr. Barnes was very specific about what the trustees were to do with his assets: He wanted them to remain housed in his small, meticulously conceived institution in the Philadelphia suburb of Merion, never to be loaned out or sold to other museums. He wanted the Barnes trustees to continue his educational mission. And most of all, he wanted to make sure the corporate foundations and politicians in Philly didn’t get their grubby paws on it. The Art Of The Steal is about how Barnes’ seemingly ironclad wishes were withered away by unscrupulous trustees, coffer-draining legal battles, and the overwhelming force of a city looking to bring in the tourist dollar. There are two sides of the story—the other being that the Barnes Foundation simply didn’t have the capital to be a sustainable entity—but the film makes its allegiances clear. And that’s not a bad thing: In this David and Goliath story, Goliath kicks the ever loving shit out of David, and the film is convincing and righteous in its advocacy. It also leaves you with troubling questions about the runaway commodification of art, the extent to which it does or does not belong the public, and just how much power the individual really has in society. Grade: B

Toronto Film Festival ’09: Day 4 [AV Club].